INSPIRATIONAL SURFSKI PADDLER SET FOR ASTONISHING NEW CHALLENGE

It was a passing conversation that redirected the course of Jonathan White’s life.

The year was 2018.

Eight years since, while commanding a foot patrol in Afghanistan with the British Royal Marines, he stepped on a homemade roadside bomb.

“Basically, there and then, it amputated both of my legs above the knee and my right arm above the elbow,” he recalls.

And six years since, against all odds, he made a return to kayaking and completed the 125-mile ‘Devizes to Westminster’ – the world’s longest non-stop canoe race.

“I was watching my eldest son George play cricket and was sitting next to one of the other dads in the team who keeps himself in good shape,” he recalls.

“He asked me, ‘What do you do you get your competitive kick now?’

“I told him, ‘No I don’t have any competitive mojo anymore, I’ve lost it.’

“We kept talking and I was telling him about perhaps getting back into kayaking again, and doing the Devizes to Westminster race and go sub-24 hours and stuff like that.

“At the end he just said to me, ‘I think you’re talking rubbish about not having your competitive mojo.’

“Two weeks later, I bought a boat and that was it.”

Jonathan was no stranger to a kayak.

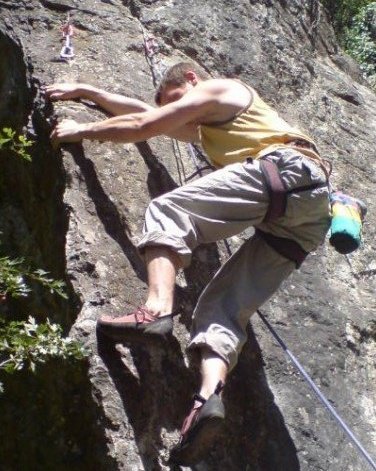

He’s always had a fascination with the outdoors, and at school was a keen climber, often going out with his dad.

“One of my geography paddlers came to me and said, ‘if you enjoy climbing, you’ll probably love paddling,’ he says.

“It all really started when I was 13, really, in the school swimming pool which was 15 metres long… just doing low brace after low brace, high brace after high brace.

“As we got better, we started going out and doing trips on the local rivers.”

“I used to disappear in the mountains around the UK on my own for a few days, and not tell anyone where I was going.

“I got myself into all sorts of mini dramas and somehow got myself out of it… I used to get a real buzz out of that,” he laughs.

Even while on tour in the Middle East, without fail, he’d complete 100 pull-ups each and every day.

“It’s one of those things I’ve always needed for my sanity.”

So, it’s no surprise that he jumped at the first available opportunity to get back to doing what he loves – even if it was just nine weeks after suffering his injuries.

“An old friend of my dad’s who I knew through kayaking came to visit me, and he asked the question, ‘do you think you could get in the boat again?’

“I said, ‘Yeah, potentially… I’m sure we could do something.’

“And it all went from there.”

In a sign of coincidence, or perhaps something more, the recovery centre where Jonathan was being treated at the time of that conversation actually had a kayak ergo.

“The first time we got on this thing, we literally strapped my hand onto the paddle with bungee and tape and stuff like that.”

“It was the only cardiovascular exercise I could do without wrecking my body.

“If I got on a hand-bike, having only one arm, within 10 minutes my left shoulder was absolutely done in.

“I couldn’t do things like running, because my legs were in such a bad way… it was the only thing that I could naturally do.”

Jonathan threw himself into it.

So much so, that not long after, he began dreaming big.

“I’m not sure how it came about, but we ended up deciding to do the Devizes to Westminster race.”

For the uninitiated, the ‘DW’ is the world’s longest non-stop canoe race. Competitors race in K2’s over 125 miles – 200 kilometres – usually taking around 24 hours to reach the Westminster Bridge in the heart of London.

It’s regarded as one of the most gruelling events on the calendar, but Jonathan was undaunted – even with an extra couple of hurdles thrown in, for good measure.

“Initially I started training with my then wife, but six weeks before the race we realised she was pregnant, and it probably wasn’t the best idea for her to be doing it.

“A mate of mine Lee jumped in the boat with me, and we only did around 119 miles of training together.”

It was far from an ideal preparation, yet less than two years after Jonathan’s accident, the pair reached the finish line.

“It was cool for both of us, but Lee found a passion for kayaking again, and actually left the Mariners and went on to be a sea kayaking guide, which he absolutely loves.

“Whereas I basically didn’t sit in the boat for seven years.

“Life got busy trying to build a house and build my business, and that was that.”

On the surface, Jonathan’s fire had all but gone out.

“Everyone used to ask me about competition, but I used to say that I wasn’t competitive anymore, I’d lost my mojo and was focusing on business and stuff like that.”

It coincided with a tough period in his life.

Between 2015 and 2017, he underwent 17 separate reconstructive surgeries.

“It was a pretty horrendous time,” he admits.

But that’s when it all clicked.

That night at cricket training, something changed – and his life would never be the same.

Jonathan White has never been one to take the easy option, but this time around, he somehow raised the bar even further.

After searching on eBay for a suitable boat, he ended up settling on a racing K1.

“I thought, ‘You know what? It’s the only one in my price range, I’m going to take the pain and learn how to paddle it.’

“I still remember the look on the guy’s face when I turned up to his house and picked it up… he said, ‘Do you know what you’re buying?’”

“I just went for it.”

He was out of the water training six days a week, and slowly, day by day, began to see improvement.

Each small milestone was celebrated, like in the below video where he managed to paddle 50 metres before falling in.

“I was actually surprised that I got that far in three sessions!” He laughs.

His improvement was exponential, and it wasn’t long before he signed up for a marathon kayak race, where he crossed paths with Jim Taylor-Ross – the UK’s Epic Dealer and Team Manager of the Great Britain national surfski team.

“He just grabbed me after a race and said, ‘the flatwater stuff is cool, but you’ll get a real buzz out of doing surfski.’”

“We didn’t have a clue how any of it was going to work with prosthetics and leg-length and stuff.

“The test was really to see whether I could sit in the ocean, and if I fall out, can I get back in.”

It’s a test he passed, setting off a whirlwind progression.

His next paddle in a surfski was the 2019 Epic Bay Ocean Race in Exmouth.

Two after that, was the 2019 ICON Classic – Britain’s largest downwind event.

Conditions weren’t quite suitable for a beginner. So strong was the wind, and so vicious were the tides, that race organisers were on edge.

“Before the race, Mark [Ressel] said in the briefing, ‘If you’re a newbie to surfski and you haven’t done that much before, I’ll give you your money back. This is not the day to be brave.’

“I looked at my safety paddler and Jim and said, ‘How much of a newbie do you have to be to not do it!?’

“They said, yeah yeah, you’ll be fine’… I spent most of that race swearing!”

Within the space of half a dozen surfski paddles, Jonathan was hooked.

He had been bitten by the surfski bug and began planning races around Europe.

“I was never a good swimmer, I was always quite nervous around the sea and the ocean,” he admits.

“I see the amazing comfort that the guys who grew up in surf lifesaving have and I don’t think I’ll ever get there.

“But for me, it’s a great replacement for climbing in the mountains… it’s that ‘you versus nature’ bit.

“Being on your own, versing nature, and coming out of it – there is that element to surfski, which is super cool.”

“Then there’s also the feeling of trying to chase and catch waves, which is really similar to skiing.

“And even with rugby, you’re looking at how everything around you is moving, you’re trying to spot how to deal with it then deal with the actions because of it.

“You get all of that on the ocean, and that’s really cool.”

He also found that it began influencing his work, where he is a leadership coach to high-flying businessmen and women.

“A lot of people talk about using meditation to achieve mindfulness and that sort of thing, but I could never get into it.

“When they describe mindfulness, I tell them, ‘that’s paddling for me.’”

“There’s something about the concentration, the technique, stroke after stroke and trying to get it right each time, that just clears your head.

“When I have time off training, I notice the difference right away.

“As soon as I start again, that’s when my work performance picks back up, I relax and deal with stress and get on top of things.

“I’ve always found that really interesting – get training back on track, and things will fall into place.”

He’s enjoyed a meteoric rise, but Jonathan White’s paddling journey is far from over.

Now 37 years old, he’s eyeing off a new challenge – and they don’t come any bigger.

Canoe racing was added to the Paralympic program in 2016 and has soared in popularity since.

Australian Curtis McGrath won the inaugural KL2 gold medal, sharing a near-identical story to that of White, having lost both of his legs while on tour in Afghanistan.

And that’s where Jonathan wants to find himself – on the start line of the Paris 2024 Games, even if he is at a disadvantage due to the current classification system.

“When I first started saying it’s what I wanted to do, everyone said, ‘It’s a nice idea, but everyone else has got two arms, you don’t stand a chance,’” he says.

“’Too injured to compete’… that’s what it felt like everyone was saying to me.”

“At the moment, given the way I’m progressing, I feel like it is achievable.”

But to get there, he’s going to need to invest – both in terms of effort and commitment, as well as financial support.

Jonathan has just launched a fundraising campaign, which you can view and support here.

Money raised will cover his prosthetic equipment, training and trip expenses, while a portion of it will also go to the Royal Marines Charity.

“There are guys that need a lot more support than me, and they’re out there doing their best for them,” he explains.

“The charity doesn’t just throw money at a problem, they’re really good at solving them.

“They don’t waste money, instead they’re there as a safety net.”

Even if his Olympic dream takes flight, he knows that he won’t be stepping away from surfski paddling to focus on kayaking.

“I think everyone imagines these big surfski races are long steady endurance events like marathon running, which of course, they’re not.

“When you’re chasing a wave, you don’t give up until the wave is completely gone.

“I find I push myself much harder when I’m chasing a wave, and I don’t even realise it because I’m enjoying myself so much.

“It’s just awesome fun.”

Paddling has now formed a central role in Jonathan’s life – and that won’t change anytime soon.

He’s now looking to complete his coaching qualifications so that he can share the gift with others, adamant he won’t ever step away from the sport, like he did those years ago.

“I was just lying to myself and everyone else around me about who I am and what made me tick,” he admits.

“I get it – you need to have other goals as well, but I definitely missed training and that competitive edge to it.

“That was six years of my life where I got it wrong.

“It’s the little things – once or twice a week, the kids will walk or cycle along the canal while I’m training, so they get to see me train.

“I’m quicker on the water than I am on the land, so it means they can go out and have a good time and I can keep up with them, which I can’t do on my feet.

“I think it’s going to be a part of my life now for a long, long time.”

And all because of a chance encounter.

Jonathan hasn’t had the chance to catch up with that cricketing father, who unknowingly pushed him back into the boat.

He often sees him from a distance though, running along the bank of the canal while he’s in his kayak, oblivious to just how much he’s reshaped his life.

“I’m not quite sure if he realises what a big effect he had on me in that conversation.

“At some stage we’ll catch up, and I’ll let him know.”