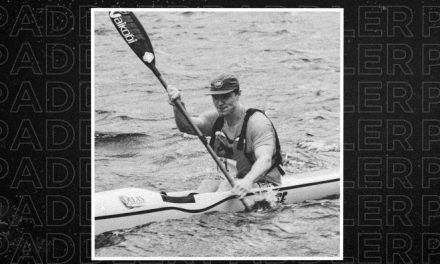

THE PADDLER’S PROFILE: TIM HORAN

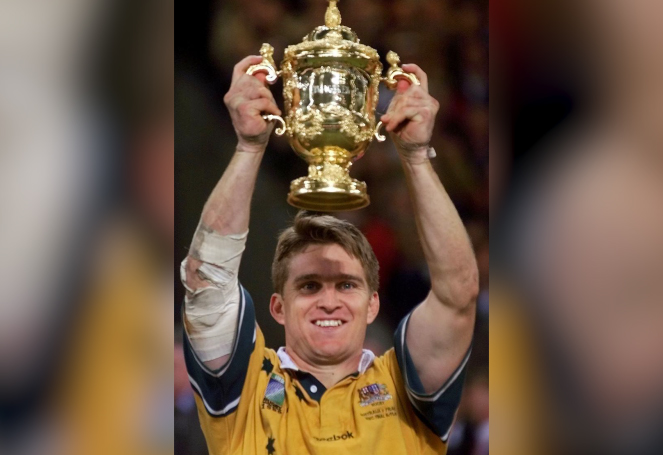

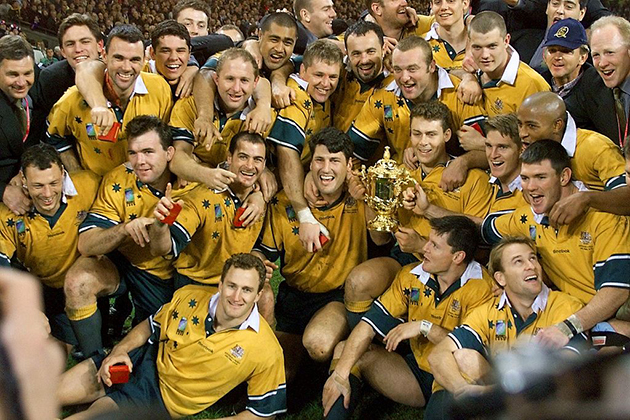

In 1999, Tim Horan held the Webb Ellis Trophy aloft having completed one of rugby’s greatest fairytale comeback stories.

Australia had just beaten France 35 to 12 in front of more than 70,000 fans, and hundreds of millions watching worldwide.

It was Horan’s second Rugby World Cup win and he would soon be named ‘Player of the Tournament’ for his breathtaking campaign – an achievement made even more remarkable given the adversity he overcame to get there.

Among rugby fans, the story is well-known.

Five years earlier, the electrifying centre was playing for the Queensland Reds in the Super 10 final in Durban when he suffered what many expected would be a career-ending knee injury.

In an instant, he tore his cruciate and medial ligaments, tore his cartilage and dislocated his patella.

Anecdotally, it was found floating somewhere behind his hamstring.

The extent of damage was so horrific that it was feared he would never be able to run again.

But what few people know is the role surfski paddling played in helping him return to the top of the sport.

“I had to try and find other ways to keep up my fitness,” Horan explains to The Paddler.

“I bought a Forcefield surfski from Dwayne Thuys and Trevor Hendy and they took me out a few times for some lessons through Currumbin Alley.

“It took me a while to even get out past the first couple of waves… but falling in was all part of it to understand the balance of the ski and the core stability that you needed.”

“I played a little bit of tennis, which was good to get back to stopping and starting movement back into my knee.

“But I found the paddling side of things really important… I never lifted in the gym, I didn’t really enjoy lifting weights.

“So, in terms of upper body strength and fitness wise, I decided to start ski paddling in those days.”

Horan has now been paddling surfskis for more than 25 years.

The fact that Horan turned to a new sport during the height of his professional career may surprise a lot of readers.

But paddling wasn’t a foreign challenge.

Having grown up in Brisbane, Horan spent plenty of time on the picturesque beaches of the Gold Coast.

“As a family, Dad bought an old wave ski, so I was paddling and catching waves on those around the 12, 13 and 14 age group,” he says.

“I had that sort of experience in a boat, but I had never paddled on a longer racing ski.”

Tim missed the entire 1994 season but recovered in time to feature in Australia’s 1995 Rugby World Cup campaign.

Although the sport soon entered its professional era, his paddling didn’t stop.

“It was mainly in summer during our off-season,” he recalls.

“That time off got shorter and shorter as professional rugby came into it – we’d finish in mid-November then you’d be back on the training paddock in January.

“But I used paddling to try and stay fit so it wasn’t too much of a gap when you came back.”

Horan went on to achieve all there was to achieve in the sport.

Two World Cup wins from his three campaigns, a ‘Player of the Tournament’ honour, 80 Wallabies appearances and 30 tries to go with them – it’s no surprise he’s an inductee to the World Rugby Hall of Fame.

His iconic try, finishing David Campese’s ‘overhead’ pass in the 1991 World Cup, is still one of the most revered in the game’s history.

Having played sport at the very highest of levels, he was aware that he needed something to help fill the void when he retired in 2000.

“I just thought I needed a challenge to keep me mentally and physically fit,” Horan says.

“I was in my thirties and couldn’t do a lot of running because of a bad foot injury from the last couple of years in my career, and the knee still wasn’t great.

“I couldn’t run a lot and didn’t want to go to the gym, so I recognised it was a great way to keep active.

“So, I really took up paddling a bit more seriously then.”

Along with a group of longtime friends, including Patrick Dixon who he’s now paddled alongside for 20 years, Horan began to find a routine with his paddling.

Two or three times a week, they’d paddle on the river in Brisbane clocking around 12 kilometres, before getting in the surf on the weekends, usually on the Gold Coast.

It was a steep learning curve.

“I think in the early days, paddling out from Currumbin down to Burleigh Heads and having a few falls off the ski out near the shark nets, you learn to get on pretty quickly,” he laughs.

“Silly enough, I decided in 2006 to do the teams event of the Coolanagatta Gold, paddling 23 kilometres from Surfers Paradise to Coolangatta.

“I’d done a lot of paddling building up to that time, but on the day I think it was blowing a 25 knot easterly wind.”

“And obviously in a teams’ event, everyone stacks their teams so there was something like two or three Olympic paddlers and all these retired ironmen… I think I beat one home.”

Horan never expected to be at the front-end of the field, but after a lifetime of elite sport, he admits there was still some competitive fire burning within him.

“It was probably a bit frustrating because you knew you never were going to be the best in your field because the other guys had been doing it for so long and I was just an amateur, mid-week paddler.”

“When you come from professional sport where you’re at your peak at a certain level… you’re then trying not just to keep up in the Coolangatta Gold, but actually just finish it.”

“That was a different experience.”

He’s quick to point out that feeling certainly didn’t motivate his paddling.

“You never lose your competitive juices, I suppose.,” he admits.

“But it’s funny, when I finished rugby I started playing a bit of touch footy.

“Even that was difficult because there’s always people that want to beat you or run around you.

“I know my limitations on paddling – I’ve been out in some pretty big swell and caught some pretty big waves… but you only need a few falls in the surf at six o’clock at night, trying to get back onto the beach, to slow you down a bit.”

“You get to a stage where you only go to these competitions just for something to work towards.

“You’re not trying to win or get a personal best time… you do it to give you something to train for.”

In fact, removing himself from that competitive-atmosphere is part of the attraction.

“I think it’s therapeutic… you can go at your own pace,” he says.

“You can paddle on the river, you can paddle on a creek and you can go and catch waves.

“Most of the time you’ve got control over what you’re doing.”

After a lifetime of high-impact collisions on his body, the other obvious benefit to paddling is its low-impact movement.

“It has very limited pounding on your knees and ankles,” Horan explains.

“You can paddle in a group and chat to people along the way, or train really hard and then chat at the end of a session… I’ve really enjoyed it over my period of time.”

“I’ve really noticed in the past five years just how popular it’s getting.

“When I’m down in Sydney sometimes I’ll hire a boat and go for a paddle in the harbour… nowadays, there’s just so many more people doing it.”

For Tim, that’s a frequent occurrence.

On top of his professional career, he still has a strong presence in Australian rugby as a commentator for Channel Nine and Stan Sport.

And he’s thankful he can use those skills he developed within the game – and the experiences he’s had along the way – in other facets of his life.

Paddling is one of those beneficiaries.

“Probably just knowing your limits, I think.” He explains. “Being able to push yourself that little bit harder.

“The great thing about professional sport in rugby is that you’re playing in big stadiums around the world with tens of thousands of people watching.

“But I like the peacefulness of paddling where no one is watching… you’re just against yourself.”

“You can go as hard as you like, or you can go as easy as you’d like.

“Some days we’ve stayed out there catching waves for three hours, other days we go out for half an hour and it’s too rough so you come in.

“I do it to stay mentally fit… that’s the main reason why I enjoy it.”